Thermal expansion

| Thermodynamics | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Thermal expansion is the tendency of matter to change in volume in response to a change in temperature.[1] All materials have this tendency.

When a substance is heated, its particles begin moving and become active thus maintaining a greater average separation. Materials which contract with increasing temperature are rare; this effect is limited in size, and only occurs within limited temperature ranges. The degree of expansion divided by the change in temperature is called the material's coefficient of thermal expansion and generally varies with temperature.

Contents |

Overview

Predicting expansion

If an equation of state is available, it can be used to predict the values of the thermal expansion at all the required temperatures and pressures, along with many other state functions.

Contraction effects

A number of materials contract on heating within certain temperature ranges; this is usually called negative thermal expansion, rather than "thermal contraction". For example, the coefficient of thermal expansion of water drops to zero as it is cooled to roughly 4 °C and then becomes negative below this temperature, this means that water has a maximum density at this temperature, and this leads to bodies of water maintaining this temperature at their lower depths during extended periods of sub-zero weather. Also, fairly pure silicon has a negative coeffcient of thermal expansion for temperatures between about 18 kelvin and 120 kelvin.[2]

Some substances expand when cooled, such as freezing water, so they have negative thermal expansion coefficients.

Factors

Unlike gases or liquids, solid materials tend to keep their shape when undergoing thermal expansion.

Thermal expansion generally decreases with increasing bond energy, which also has an effect on the hardness of solids, so, harder materials are more likely to have lower thermal expansion. In general, liquids expand slightly more than solids.

Absorption or desorption of water (or other solvents) can change the size of many common materials; many organic materials change size much more due to this effect than they do to thermal expansion. Common plastics exposed to water can, in the long term, expand many percent.

Coefficient of thermal expansion

The coefficient of thermal expansion describes how the size of an object changes with a change in temperature. Specifically, it measures the fractional change in size per degree change in temperature at a constant pressure. Several types of coefficients have been developed: volumetric, area, and linear. Which is used depends on the particular application and which dimensions are considered important. For solids, one might only be concerned with the change along a length, or over some area.

The volumetric thermal expansion coefficient is the most basic thermal expansion coefficient. All substances expand or contract when their temperature changes, and the expansion or contraction always occurs in all directions. Substances that expand at the same rate in any direction are called isotropic. For isotropic materials, the area and linear coefficients may be approximated to good accuracy from a known volumetric coefficient, under some circumstances.

Mathematical definitions of these coefficients are defined below for solids, liquids, and gasses.

General volumetric thermal expansion coefficient

In the general case of a gas, liquid, or solid, the volumetric coefficient of thermal expansion is given by

The subscript p indicates that the pressure is held constant during the expansion, and the subscript "V" stresses that it is the volumetric (not linear) expansion that enters this general definition. In the case of a gas, the fact that the pressure is held constant is important, because the volume of a gas will vary appreciably with pressure as well as temperature. For a gas of low density this can be seen from the ideal gas law.

Expansion in solids

All materials change their size when subjected to a temperature change as long as the pressure is held constant. In the special case of solid materials, the pressure does not appreciably affect the size of an object, and so for solids, it's usually not necessary to specify that the pressure be held constant.

Common engineering solids usually have coefficients of thermal expansion that do not vary significantly over the range of temperatures where they are designed to be used, so where extremely high accuracy is not required, calculations can be based on a constant, average, value of the coefficient of expansion.

Linear expansion

The linear thermal expansion coefficient relates the change in a material's linear dimensions to a change in temperature. It is the fractional change in length per degree of temperature change. Ignoring pressure, we may write:

where  is the linear dimension (e.g. length) and

is the linear dimension (e.g. length) and  is the rate of change of that linear dimension per unit change in temperature.

is the rate of change of that linear dimension per unit change in temperature.

The change in the linear dimension can be estimated to be:

This equation works well as long as the linear expansion coefficient does not change much over the change in temperature  . If it does, the equation must be integrated.

. If it does, the equation must be integrated.

Effects on strain

For solid materials with a significant length, like rods or cables, an estimate of the amount of thermal expansion can be described by the material strain, given by  and defined as:

and defined as:

where  is the length before the change of temperature and

is the length before the change of temperature and  is the length after the change of temperature.

is the length after the change of temperature.

For most solids, thermal expansion relates directly with temperature:

Thus, the change in either the strain or temperature can be estimated by:

where

is the difference of the temperature between the two recorded strains, measured in degrees Celsius or kelvins, and  is the linear coefficient of thermal expansion in inverse kelvins.

is the linear coefficient of thermal expansion in inverse kelvins.

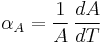

Area expansion

The area thermal expansion coefficient relates the change in a material's area dimensions to a change in temperature. It is the fractional change in area per degree of temperature change. Ignoring pressure, we may write:

where  is some area of interest on the object, and

is some area of interest on the object, and  is the rate of change of that area per unit change in temperature.

is the rate of change of that area per unit change in temperature.

The change in the linear dimension can be estimated as:

This equation works well as long as the linear expansion coefficient does not change much over the change in temperature  . If it does, the equation must be integrated.

. If it does, the equation must be integrated.

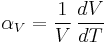

Volumetric expansion

For a solid, we can ignore the effects of pressure on the material, and the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient can be written [3]:

where  is the volume of the material, and

is the volume of the material, and  is the rate of change of that volume with temperature.

is the rate of change of that volume with temperature.

This means that the volume of a material changes by some fixed fractional amount. For example, a steel block with a volume of 1 cubic meter might expand to 1.02 cubic meters when the temperature is raised by 50 C. This is an expansion of 2%. If we had a block of steel with a volume of 2 cubic meters, then under the same conditions, it would expand to 2.04 cubic meters, again an expansion of 2%. The volumetric expansion coefficient would be 2% for 50 C, or 0.04 2% per degree, or 0.0004 C per degree.

If we already know the expansion coefficient, then we can calculate the change in volume

where  is the fractional change in volume (e.g., 0.02) and

is the fractional change in volume (e.g., 0.02) and  is the change in temperature (50 C).

is the change in temperature (50 C).

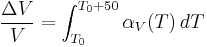

The above example assumes that the expansion coefficient did not change as the temperature changed. This is not always true, but for small changes in temperature, it is a good approximation. If the volumetric expansion coefficient does change appreciably with temperature, then the above equation will have to be integrated:

where  is the starting temperature and

is the starting temperature and  is the volumetric expansion coefficient as a function of temperature T.

is the volumetric expansion coefficient as a function of temperature T.

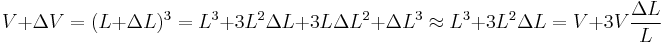

Isotropic materials

For exactly isotropic materials, the linear thermal expansion coefficient is almost exactly one third the volumetric coefficient.

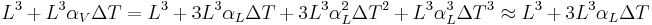

This ratio arises because volume is composed of three mutually orthogonal directions. Thus, in an isotropic material, one-third of the volumetric expansion is in a single axis (a very close approximation for small differential changes). As an example, take a cube of steel that has sides of length L. The original volume will be  and the new volume, after a temperature increase, will be

and the new volume, after a temperature increase, will be

We can make the substitutions  and, for isotropic materials,

and, for isotropic materials,  . We now have:

. We now have:

Since the volumetric and linear coefficients are defined only for extremely small temperature and dimensional changes, the last two terms can be ignored and we get the above relationship between the two coefficients. If we are trying to go back and forth between volumetric and linear coefficients using larger values of  then we will need to take into account the third term, and sometimes even the fourth term.

then we will need to take into account the third term, and sometimes even the fourth term.

Similarly, the area thermal expansion coefficient is 2/3 of the volumetric coefficient.

This ratio can be found in a way similar to that in the linear example above, noting that the area of a face on the cube is just  . Also, the same considerations must be made when dealing with large values of

. Also, the same considerations must be made when dealing with large values of

Anisotropic materials

Materials with anisotropic structures, such as crystals and many composites, will generally have different linear expansion coefficients  in different directions. As a result, the total volumetric expansion is distributed unequally among the three axes. If the crystal symmetry is monoclinic or triclinic even the angles between these axes are subject to thermal changes. In such cases it is necessary to treat thermal expansion as a tensor that has up to six independent elements. A good way to determine the elements of the tensor is to study the expansion by powder diffraction.

in different directions. As a result, the total volumetric expansion is distributed unequally among the three axes. If the crystal symmetry is monoclinic or triclinic even the angles between these axes are subject to thermal changes. In such cases it is necessary to treat thermal expansion as a tensor that has up to six independent elements. A good way to determine the elements of the tensor is to study the expansion by powder diffraction.

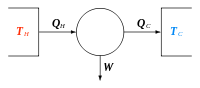

Expansion in gasses

For an ideal gas, the volumetric thermal expansivity (i.e. relative change in volume due to temperature change) depends on the type of process in which temperature is changed. Two known cases are isobaric change, where pressure is held constant, and adiabatic change, where no work is done and no change in entropy occurs.

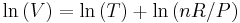

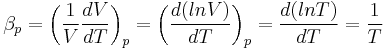

In an isobaric process, the volumetric thermal expansivity, which we denote  , is:

, is:

The index  denotes an isobaric process.

denotes an isobaric process.

Expansion in liquids

Theoretically, the coefficient of linear expansion can be approximated from the coefficient of volumetric expansion (β≈3α). However, for liquids, α is calculated through the experimental determination of β.

Examples and Applications

The expansion and contraction of materials must be considered when designing large structures, when using tape or chain to measure distances for land surveys, when designing molds for casting hot material, and in other engineering applications when large changes in dimension due to temperature are expected.

Thermal expansion is also used in mechanical applications to fit parts over one another, e.g. a bushing can be fitted over a shaft by making its inner diameter slightly smaller than the diameter of the shaft, then heating it until it fits over the shaft, and allowing it to cool after it has been pushed over the shaft, thus achieving a 'shrink fit'. Induction shrink fitting is a common industrial method to pre-heat metal components between 150 °C and 300 °C thereby causing them to expand and allow for the insertion or removal of another component.

There exist some alloys with a very small linear expansion coefficient, used in applications that demand very small changes in physical dimension over a range of temperatures. One of these is Invar 36, with α approximately equal to 0.6×10−6/°C. These alloys are useful in aerospace applications where wide temperature swings may occur.

Pullinger's apparatus is used to determine linear expansion of a metallic rod in laboratory. The apparatus consists of a metal cylinder closed at both ends (called a steam jacket). It is provided with an inlet and outlet for the steam.The steam for heating the rod is supplied by a boiler which is connected by a rubber tube to the inlet. The center of cylinder contains a hole to insert a thermometer. The rod, under investigation, is enclosed in a steam jacket. Its one end is free, but the second end is pressed against a fixed screw. The position of the rod is determined by a micrometer screw gauge or spherometer.

The control of thermal expansion in ceramics is a key concern for a wide range of reasons. For example, ceramics are brittle and cannot tolerate sudden changes in temperature (without cracking) if their expansion is too high. Ceramics need to be joined or work in consort with a wide range of materials and therefore their expansion must be matched to the application. Because glazes need to be firmly attached to the underlying porcelain (or other body type) their thermal expansion must be tuned to 'fit' the body so that crazing or shivering do not occur. Good example of products whose thermal expansion is the key to their success are CorningWare and the spark plug. The thermal expansion of ceramic bodies can be controlled by firing to create crystalline species that will influence the overall expansion of the material in the desired direction. In addition or instead the formulation of the body can employ materials delivering particles of the desired expansion to the matrix. The thermal expansion of glazes is controlled by their ceramic chemistry. In most cases there are complex issues involved in controlling body and glaze expansion, adjusting for thermal expansion must be done with an eye to other properties that will be affected, generally trade-offs are required.

Heat-induced expansion has to be taken into account in most areas of engineering. A few examples are:

- Metal framed windows need rubber spacers

- Rubber tires

- Metal hot water heating pipes should not be used in long straight lengths

- Large structures such as railways and bridges need expansion joints in the structures to avoid sun kink

- One of the reasons for the poor performance of cold car engines is that parts have inefficiently large spacings until the normal operating temperature is achieved.

- A gridiron pendulum uses an arrangement of different metals to maintain a more temperature stable pendulum length.

- A power line on a hot day is droopy, but on a cold day it is tight. This is because the metals expand under heat.

Thermometers are another application of thermal expansion — most contain a liquid (usually mercury or alcohol) which is constrained to flow in only one direction (along the tube) due to changes in volume brought about by changes in temperature. A bi-metal mechanical thermometer uses a bimetallic strip and registers changes due to the differing coefficient of thermal expansion between the two materials.

Thermal expansion coefficients for various materials

This section summarizes the coefficients for some common materials.

In the table below, the range for α is from 10−7/°C for hard solids to 10−3/°C for organic liquids. α varies with the temperature and some materials have a very high variation.

Theoretically, the coefficient of linear expansion can be approximated from the coefficient of volumetric expansion (β≈3α). However, for liquids, α is calculated through the experimental determination of β, so it is more accurate to state β here, rather than α.

(The formula β≈3α is usually used for solids.)[4]

| Material | Linear coefficient, α, at 20 °C (10−6/°C) |

Volumetric coefficient, β, at 20 °C (10−6/°C) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminium | 23 | 69 | |

| Benzocyclobutene | 42 | 126 | |

| Brass | 19 | 57 | |

| Carbon steel | 10.8 | 32.4 | |

| Concrete | 12 | 36 | |

| Copper | 17 | 51 | |

| Diamond | 1 | 3 | |

| Ethanol | 250 | 750[5] | Linear value is approximate |

| Gallium(III) arsenide | 5.8 | 17.4 | |

| Gasoline | 317 | 950[4] | Linear value is approximate |

| Glass | 8.5 | 25.5 | |

| Glass, borosilicate | 3.3 | 9.9 | |

| Gold | 14 | 42 | |

| Indium phosphide | 4.6 | 13.8 | |

| Invar | 1.2 | 3.6 | |

| Iron | 11.1 | 33.3 | |

| Lead | 29 | 87 | |

| MACOR | 9.3[6] | ||

| Magnesium | 26 | 78 | |

| Mercury | 61 | 182[7] | Linear value is approximate |

| Molybdenum | 4.8 | 14.4 | |

| Nickel | 13 | 39 | |

| Oak | 54 [8] | 162 | Perpendicular to the grain |

| Pine | 34 | 102 | Perpendicular to the grain |

| Platinum | 9 | 27 | |

| PVC | 52 | 156 | |

| Quartz (fused) | 0.59 | 1.77 | |

| Rubber | 77 | 231 | |

| Sapphire | 5.3[9] | Parallel to C axis, or [001] | |

| Silicon Carbide | 2.77 [10] | 8.31 | |

| Silicon | 3 | 9 | |

| Silver | 18[11] | 54 | |

| Sitall | 0.15[12] | 0.45 | |

| Stainless steel | 17.3 | 51.9 | |

| Steel | 11.0 ~ 13.0 | 33.0 ~ 39.0 | Depends on composition |

| Tungsten | 4.5 | 13.5 | |

| Water | 69 | 207[7] | Linear value is approximate |

See also

- Autovent

- Grüneisen parameter

References

- ↑ Paul A., Tipler; Gene Mosca (2008). Physics for Scientists and Engineers, Sixth Edition, Volume 1. New York, NY: Worth Publishers. pp. 666–670. ISBN 1-4292-0132-0. http://books.google.com/books?id=BMVR37-8Jh0C&pg=PA668&dq=%22Physics+for+Scientists+and+Engineers%22+tipler+%22thermal+expansion%22&as_brr=3&cd=1#.

- ↑ William C. O'Mara; Robert B. Herring; Lee P. Hunt, eds. (1990), Handbook of semiconductor silicon technology, Park Ridge, New Jersey: Noyes Publications, p. 431, ISBN 0-8155-1237-6, http://books.google.com/books?id=COcVgAtqeKkC&pg=PA431&dq=silicon+negative+%22coefficient+of+thermal+expansion%22&hl=en&ei=XoI5TNK7MYW8sQOO4rBR&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CDgQ6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=silicon%20negative%20%22coefficient%20of%20thermal%20expansion%22&f=false, retrieved 2010 -07-11 Chapter 6 by W. Murray Bullis.

- ↑ Turcotte, Donald L.; Schubert, Gerald (2002). Geodynamics (2nd Edition ed.). Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-66624-4.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Thermal Expansion

- ↑ Textbook: Young and Geller College Physics, 8e

- ↑ http://www.corning.com/docs/specialtymaterials/pisheets/Macor.pdf

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Properties of Common Liquid Materials

- ↑ WDSC 340. Class Notes on Thermal Properties of Wood

- ↑ http://americas.kyocera.com/kicc/pdf/Kyocera%20Sapphire.pdf

- ↑ Basic Parameters of Silicon Carbide (SiC)

- ↑ Thermal Expansion Coefficients

- ↑ Star Instruments

External links

- Glass Thermal Expansion Thermal expansion measurement, definitions, thermal expansion calculation from the glass composition

- Water Expansion Calculator Water thermal expansion calculator

- DoITPoMS Teaching and Learning Package on Thermal Expansion and the Bi-material Strip

- Engineering Toolbox – List of coefficients of Linear Expansion for some common materials

- Article on how β is determined

- MatWeb: Free database of engineering properties for over 79,000 materials

- Clemson University Physics Lab: Linear Thermal Expansion

- USA NIST Website - Temperature and Dimensional Measurement workshop

- Hyperphysics: Thermal expansion

- Understanding Thermal Expansion in Ceramic Glazes